SaskDispatch.com is live! Thanks to everyone whose support made it possible for us to launch our very own website. We’re proud of our connection to our sister publication Briarpatch, but we’re excited to become more independent. And that’s part of the reason we’re looking for readers to become monthly supporters. Right now, the Sask Dispatch is produced on a part-time basis, and it’s time for us to get bigger, to write more stories, do more in-depth investigations, and reach more readers across the province. We’re looking for 50 readers to commit to monthly donations to help us work toward creating a permanent, full-time role for an editor/reporter. This will help us do more original reporting, work with more emerging and established writers, and grow the Dispatch’s reach. If you can support us with a monthly donation, thanks! And if you can’t, we’re just glad you’re with us as a reader.

Valerio Donfrancesco via Flickr

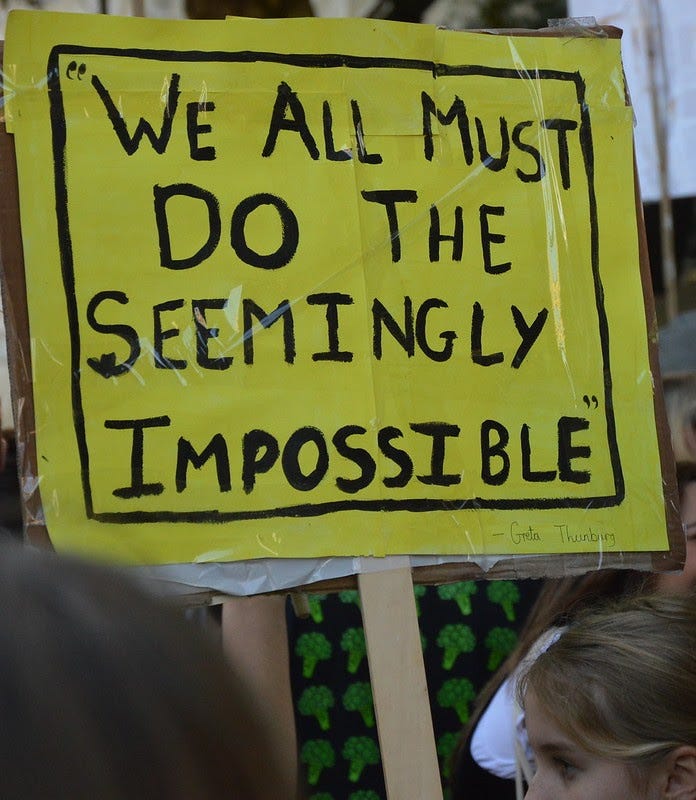

Palliative care for humanity

On Monday the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a devastating report on the current and projected state of the global climate. After years of warnings that humanity was on the verge of climate change, the IPCC’s report made clear what many already knew: climate change isn’t coming, it’s here. And while the report doesn’t pull any punches when it comes to pointing the finger at humans, the IPCC was much less willing to identify the capitalist and imperialist structures that are truly responsible for the situation that we’re in, a sign that we still, as a society, struggle to face the facts of this crisis.

Saskatchewan has the highest per-capita emissions in Canada, coming in ahead of even Alberta, like the province is a trapezoidal coal-spewing dungeon lodged underneath hell’s literal basement. Not only is the province one of the leading greenhouse gas emitters globally, but we’re feeling the effects of climate change ourselves. Large parts of Saskatchewan have burned this summer, with the province recording more than double the number of fires than in an average year. The places that aren’t on fire are seeing air quality advisories and record numbers of smoke days, and the prolonged drought situation has led to a dire crop forecast for farmers and the funny-not-funny warning that “hay crimes” may be on the rise.

David Evans via Flickr

Journalists and organizations have, and will continue to, write about the report, what it means, and what needs to be done if we are to stop the situation from worsening. One thing that is talked about less commonly, is palliative care for humanity.

When the subject of palliative care is brought up, it can arouse a lot of emotions, particularly anger towards whoever has raised the subject, be they physicians, family members, or the patient themselves. The phrase suggests a surrender to disease. It can seem, at first glance, as submission to despair. But palliative care doesn’t mean giving up. It is a hard shift in the way we live with disease. It means recognizing that we are living with a serious, life-threatening illness and that that illness may kill us. Palliative care requires accepting the seriousness of our condition, and doing what we can to alleviate the symptoms that we are experiencing and that we anticipate experiencing. It means frankly assessing what we have lost and will lose and making a plan for how to live joyfully and with as little pain as possible in spite of those losses. For people living with cancer or organ failure or another life-threatening illness, palliative care can mean pain management. It means spiritual and social care. It means guidance on how to have difficult and painful conversations about the reality of your condition with loved ones. It means taking honest stock of your options, giving up on unrealistic expectations or useless treatments and finding a new way forward.

It means accepting that your life will never be the same.

Jim Forrest via Flickr

Palliative care for humanity will look similar to this. In addition to fighting for divestment from fossil fuels and the end of capitalism and imperialism, we need to create spaces where we can gather and mourn what we have lost, and what we will lose in the future. We need to learn how to manage the pain we are in as individuals and collectives, to hold space for the rage and the grief and catastrophic anguish that we feel. We need to reflect on the remedies we have been pursuing and abandon the ones that are no longer realistic. There is no template for these kinds of discussions, but we need to develop one. We need to learn to speak frankly with one another, even when those conversations are extremely distressing. We need to anticipate the failure of systems that have not yet given out, and develop a plan and a strategy for what we will do when those systems inevitably do fail. We need to create local seed banks and information-sharing networks that can survive long-term power outages or the loss of internet connectivity, and we need to teach one another how to grow food, build and repair shelter, perform first aid, and other things that we have for too long treated as commodities for purchase. We need to anticipate how we will keep community members safe when we lose power for long periods, or when natural disaster inevitably strikes. We need to learn to live alongside this illness, because it will be with us for a long time, longer than the lifespan of anyone reading this newsletter. Perhaps ironically, the only way for this illness to be survivable is for us to recognize and accept the gravity of it. This may kill us.

There are important things that need to be done on the provincial, international, and national levels. Palliative care doesn’t mean abandoning all hope of arresting this crisis. People will need to continue to fight - fiercely - for the end of capitalism and colonialism. Ending the extraction of oil and gas only becomes more important with each passing day. Land Back and a commitment to restoring good relations between peoples and between humans and the environment is an imperative of our time, not only because it is necessary for the stability of the climate and the future of human existence, but because it is necessary for our spiritual and psychological health. It is the only ethical way forward. But as we work to restore proper relations, we also need to be preparing for the worst, and that work is work that will need to be done on a local level. The system we live in right now cannot (will not) care for everyone, and the worse the climate gets, the more people will need care. Look to the structures, like neighbourhood associations and community centres, that exist in your communities and try to determine how they can be used to prepare people for the coming struggle. How can they be used as communication hubs in the event of long-term outages? How can they be used as centres to educate people on how to grow food, survive natural disaster, and resist the police state? How can we build better, more resilient communities that will make life worth living as our current way of life collapses? If no such structures exist, what do you need to build them? We can’t rely on anyone but each other.

Project Community Care via Flickr

For all its faults - and there are many - Saskatchewan also has a long history of cooperating in times when the rest of the world was inaccessible or indifferent to us. When people have survived in this region it has been because of other people. And when people have starved in this region, it has been because of other people, too. Humans can survive this, can even come out better for it. But we can only do that if we accept the totality of the threat that we are facing. And while humanity itself can survive climate change, if the correct actions are taken swiftly and decisively, many, many individual humans will die because of it, no matter what we do now. If we take a palliative approach to our survival and accept that death is in the cards, we can mitigate the suffering that is coming, and we can lay the foundation for something better. But we can only survive this if we accept that we might not survive this.

Saskatchewan needs more independent journalism. But without the backing of corporations like Postmedia, we rely on your support to keep producing high-quality journalism that challenges the mainstream media consensus. Donate now to help us sustain and expand our work.