Welcome back to Dispatches from the Left, the Sask Dispatch newsletter! We took a week off last week for some self-care and now we’re ready to dive back into the issues that matter to Saskatchewan people! One of the things that matters to us at the Dispatch is helping people in the province hear the stories they need in order to make real, radical change in their communities. To that end, we’re accepting pitches for solutions journalism stories. We want to pay you to write about what people in your community are doing to make Saskatchewan a healthier, happier, safer place to live. Check out this piece on what we’re looking for. You can send your pitches to pitches@briarpatchmagazine.com and if you have any questions about pitching or whether your story qualifies as a solutions journalism story, email sara@briarpatchmagazine.com

Martin Brummel via Flickr

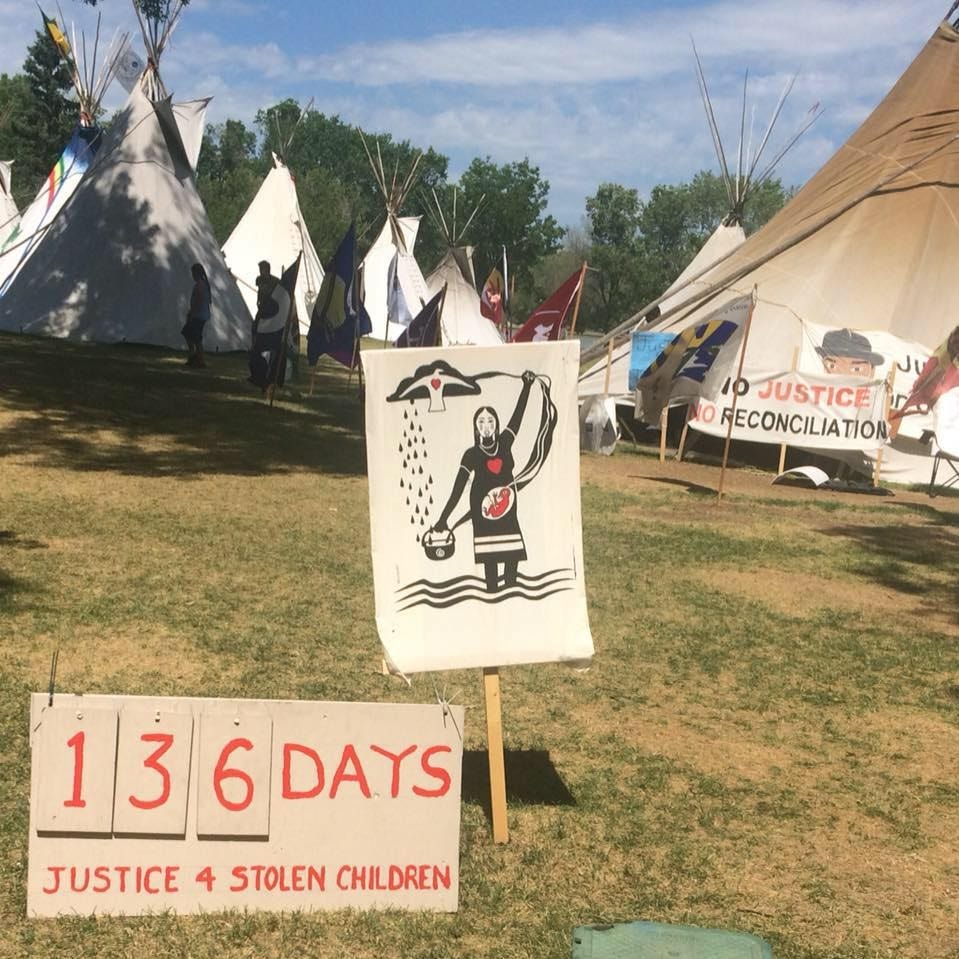

Children dying in care of the state

Saskatchewan social services has released the numbers of deaths of children in provincial care last year and the numbers are bleak. 36 children died under the province’s watch in 2020, the highest number since 2008. The government can’t yet say whether any of these deaths are related to the pandemic, but it doesn’t really matter. What matters is that more than 3,000 children were taken into state care in 2020, and 36 of them didn’t live to see the end of the year.

Certain contexts need to be considered when taking in these horrifying numbers. One is that a staggering 86 per cent of kids in care in Saskatchewan are Indigenous, as were all but one of the children who died. This is critical to understand for a couple of reasons. For one, it’s a frank indicator that the state violence against Indigenous people has not ended since the closure of the last residential school in Saskatchewan in 1996, but simply changed forms, with the government continuing its campaign of removing Indigenous children from their families and placing them where their lives are at risk. This was a major point put forward by the Justice for Our Stolen Children camp, which asserts that Indigenous children are not simply being removed from dangerous circumstances, as the state claims, but are being kidnapped from their homes by the state, which then places them in dangerous circumstances. Every effort and expense must be made to ensure that Indigenous families can stay together and live their lives without the constant threat of colonial interference. This means that, among other things, the prison industrial complex, which removes Indigenous parents from their children’s lives, must be dismantled, the drug toxicity crisis, which disproportionately affects Indigenous people, must be addressed, and safe, accessible housing must be made freely available.

Camp Justice for Our Stolen Children via Facebook

And for another, it’s an indicator of what many abolitionists say, which is that it’s not enough to replace the police with social workers (or healthcare professionals) as these groups, acting in service of the state, perpetuate many of the same indignities and violences that the police do. Death is only the most obvious traumatic impact of a life in foster care. Children who do survive the system are at increased risk of ending up criminalized, and the psychological trauma of foster care is unquantifiable. Because of austerity, public policy, and institutional racism, Saskatchewan is, for many children, a grim place to grow up. 26% of children in the province are living in poverty. That’s 73,000 kids without the financial means to thrive. It doesn’t have to be this way, and abolition is a way out that offers alternatives to incarceration, criminalization, and state brutality against children and adults.

Regina residents plan day of action for harm reduction

Saskatchewan’s second epidemic, the drug toxicity crisis, shows no signs of abating, with the province reporting 39 apparent overdose deaths in the first four months of 2021. That’s a higher rate than last year, when 379 people died, and a staggering increase from 2019, when 177 people lost their lives to drugs. While the province has allocated $2.6 million for addictions services (less money than they allocated to ice surfaces in community rinks), they have so far disregarded evidence-based approaches to harm reduction that have been brought forward by advocates and the Saskatchewan Health Authority. This includes funding for safe consumption sites, like Prairie Harm Reduction, which allows drug users to use under the observation of medical professionals, who can intervene in the case of overdose or drug toxicity.

Ekaterina Cabylis

Overdose and drug toxicity deaths are 100% preventable. No one needs to die when they use drugs, no one deserves to die from using drugs, and every time someone does lose their life to drug use, it’s a failure of the system to keep them safe from harm. Recognizing this, a group of Regina residents have planned a day of action at the Legislature for Saturday, May 8. They intend to place dozens of crosses on the lawn of the Legislative building in protest of the government’s inaction on the crisis. The group, called Regina Harm Reduction Coalition, is calling on the government to set aside the moral objections and political barriers that are currently allowing people to die needlessly.

While most of the deaths due to drug use have been labeled “overdoses,” this term is misleading. It suggests that users are being careless in their dosing, taking more than necessary. But most of these deaths are drug toxicity deaths. They’re happening because the supply of drugs is toxic and contaminated with potent additives like fentanyl. If drug users had access to a safe supply the crisis of drug toxicity deaths could largely be eliminated. Safe supply can mean many things. It’s most commonly envisioned as medical practitioners prescribing drugs to users, although that approach has barriers like limited clinical capacity, stigma, and rigid protocols that mean some people are left behind. Other approaches to safe supply include compassion clubs, biometric vending machines, and public health dispensing models that don’t require a prescription. While truly safe supply is likely a distant dream for Saskatchewan, interventions like safe consumption sites, needle exchanges, and drug testing should be (relatively) easier to obtain. Residents who are tired of the constant barrage of unnecessary deaths, which disproportionately impact Indigenous people and poor people, hope that by forcing the government and the public to confront the sheer scale of death that is being allowed, they can bring about some of these changes.

NDP presents petition to save the peatlands

In March Saba Dar wrote a piece for the Sask Dispatch about the movement to protect northern peatlands from invasive mining practices. The piece covered the critical importance of peatlands to the health of the global environment, describing the way “nature’s nurseries” capture and store carbon, generate and support astonishing biodiversity, and prevent fire and flooding. Dar’s story focused on an area of northern Saskatchewan being threatened by Lambert Peat Moss, a Quebec company whose peat mining in that province has directly contributed to devastating fires.

Quincy Miller

Lambert’s proposal to mine a tract of peatland near the Potato Lakes prompted a flurry of resistance from residents, including Kona Barreda’s seventh grade class. On April 28, Barreda’s class, which launched a petition against the project which garnered more than 20,000 signatures, got to watch as NDP MLA Doyle Vermette presented the petition before the Legislature. Although it’s unclear where things will go from here, it’s been impressive to see the grassroots actions reach the legislative floor. In a year when much of the momentum youth generated from the school strikes was lost to pandemic restrictions, it’s been particularly gratifying to see work done by youth have a real impact on the story that’s being written about the environment.

Jeremy Davis via Flickr

Children are the ones who will be reaping the worst of what climate change has to offer, and their perspective on how we need to respond to the crisis should be at the forefront. Classrooms can and should be places where students learn about the power of grassroots actions and the ways in which they can collectively influence the direction of society. Barreda has said she hopes her students “learn to stand up for themselves and fight for their land.”

Saskatchewan needs more independent journalism. But without the backing of corporations like Postmedia, we rely on your support to keep producing high-quality journalism that challenges the mainstream media consensus. Donate now to help us sustain and expand our work.